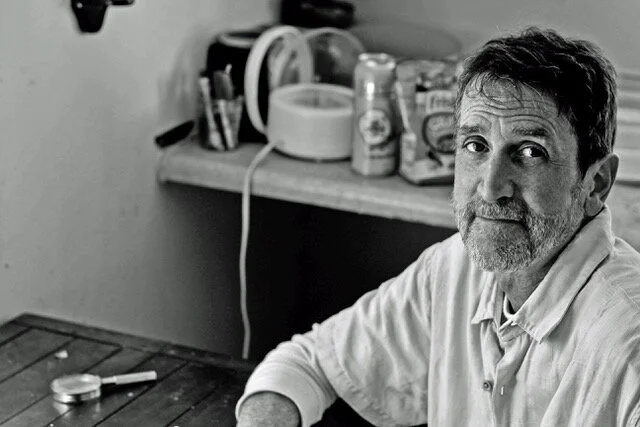

Featured Poet Carey Scott Wilkerson with Interview by Sue Walker

/Carey Scott Wilkerson, Ph.D., Georgia State University is a poet, dramatist, and opera librettist. His opera libretti and plays have been produced in Los Angeles, Atlanta, Millikin University (Decatur, IL), Pasaquan (Buena Vista, GA), and Frankfurt, Germany. (Scott has asked us to note that his opera collaborators include the composers James Ogburn, Robert Chumbley, and Angela Schwickert.) His poems have appeared in numerous journals including Negative Capability, Muse/A, The MacGuffin, Sanctuary, and The James Dickey Review. He edited (with Melissa Dickson) our anthology of Georgia Poems Stone River Sky. He is Assistant Professor of Creative Writing at Columbus State University and a member of the Core Writing Faculty in Reinhardt University’s Low-Residency Creative Writing MFA program. His new collection of poems Cruel Fever of the Sky has just been published by Negative Capability Press.

Falling

Sue Walker (SW): Your new book, Cruel Fever of the Sky, begins with “Descending Order,” a poem that slows down the fall of Icarus for the length of a sestina and serves as your opening argument. Its final line reads: “Desire is always falling from the sky.” That looks to me like the decoder ring for many of the poems in this collection. And there’s a bit of wordplay here, yes?

Carey Scott Wilkerson (CSW): Right on both counts. Desire in all its forms rains down on us from the moment we learn to dream. Moreover, to desire—the act of desiring— is to find oneself always falling, like Icarus, from some unimaginable height, having failed to do some impossible thing. I should say, by the way, that I’m not cynical about any of this. I’m essentially an optimist. I feel that the image of Icarus has been misunderstood at the margins: he’s not an arrogant brat who can’t follow instructions but, rather, a visionary who wants to live or die on his own terms. Of course, that’s probably going too far, but that’s how I see it. I also tend to make crazy statements about my own work when I can’t think up anything smart to say.

SW: Well, let’s go with that—many of the characters in these poems are observed in exactly that moment when an odd decision or “crazy statement” sets them up for a fall of some kind, a downward emotional or metaphysical trajectory, maybe a sense of helplessness, and occasionally an actual fall! Even your “realistic” poems have a vaguely surreal or dreamlike quality and the more openly surreal poems are anchored in reality.

CSW: Yes, we see a romance collapsing at the end of a Ferris wheel ride, which is connected somehow to Sisyphus and a memory of gardenias. We see The Three Little Pigs—now retired and living in a gated community—realize during a hurricane how much they miss the terror and exhilaration of life with the Big Bad Wolf. Someone has a first kiss while watching Sky Lab re-enter and blaze through the Earth’s atmosphere. And someone does in fact have an epiphany while staring at the night sky after slipping on a banana peel in a Kroger Parking lot. Is there any other place under Heaven where such a perfectly absurd event can happen? Maybe a Piggly Wiggly. Gentle surrealism is the native tongue of my poetics.

Form

SW: A mutual friend of ours, Eugenia Gaultiero, points to your facility with forms and the general idea of formal restraint in this book. Is that part of your project here?

CSW: I wish I could claim that I consciously tried to direct the energies of my poetic obsessions through elegant forms, but the truth is I just staged these poems in ways that felt intuitively correct. And sometimes, that required forms. But Eugenia is right in the sense that this book has a more intentional view of forms. It’s not news, but I’ll say it anyway: forms are magical and readily answer the call from wilder realms.

SW: What are those “wilder realms?”

CSW: Imaginative experience, dreams, Los Angeles at night, anywhere in Georgia or Alabama. All places, all spaces of beauty and mystery.

SW: Forms can be liberating, too. Don’t you find that part of the joy in working with forms is in the freedom to experiment and re-imagine certain rules?

CSW: No question about it, particularly once you begin to speak in the natural language of the form itself. Then you see possibilities open up, for instance, at the turn of a sonnet or that precarious fourth stanza of a sestina.

SW: Or the escalating problems of a terza rima!

CSW: Or poets talking shop! And you’re right about the terza rima. It’s like playing chess against oneself. Still, the game of forms is a delight. “Descending Order,” the sestina you mentioned earlier in this chat, was selected by the editors at The MacGuffin as one of the representative poems for their “all formal poetry issue” in 2020. I must admit that was gratifying. Of course, none of it would matter if there were not also interesting stories to tell. And I think the experience of falling through this book is perhaps one of one of those interesting stories.

SW: What do you mean by that?

CSW: Just that I hope this book, even in its exotic moments, hits the familiar harmonics of how life is lived at the ground level. At one point, I show Icarus falling into the lovely Chattahoochee River and then, later, eating cornbread and hot pepper jelly with a country witch. She doesn’t judge him. She repairs his wings “with the names of her favorite clouds.” That’s how we do in the South.

Fever

SW: So, we all attempt Icarus’s flight and risk that same fall?

CSW: In our own ways, yes. We’ve all come down with a cruel fever of the sky. It’s an inescapable condition of being human.

SW: Is there a cure, a vaccine? I think I know how Carey Scott Wilkerson will answer this question…

CSW: Be my guest!

SW: Art, love, and faith.

CSW: Yep. What else is there?

The Acceleration of Gravity

for Mayhaley Lancaster of Coweta County

(1875-1955: feminist, unlicensed attorney,

fortune teller, and wise mind whom many

thought to be a witch.)

It’s not later than supper when,

as from a tale no one quite believes,

Mayhaley Lancaster—seamstress, notary,

and the county’s own witch—

looks up to see Icarus splash

into the Chattahoochee River.

She rows out to meet him in a boat,

stitched together from pine splinters

and biscuit dough: it’s a conversation piece

to be sure, though strictly speaking mostly

a matter of timing as she has just set the table.

Of course, this has happened before

and is an open secret around here:

Leonardo in his proto-helicopter, the Wright Brothers,

and Santa Claus, all arrived in the same way—

wet and confused but, like Icarus, coherent enough to eat.

She pours sweet tea and salts some tomatoes.

He complains about mythology

and being trapped inside a narrative,

lost in the bog of legend.

She fills his plate with butter beans

and cornbread fried on the stove.

Icarus laments the contradictory relationship

between history and memory.

Mayhaley discovers some of last year’s

hot-pepper jelly in the back of the pantry.

He apologizes for talking so far above her head.

She forgives him for being neurotic and aloof.

Mayhaley repairs his wax wings with a quilting knot

she learned in town. Icarus signs her guestbook

both in English and in Greek. They shake hands

under the April sky in a crescent of Georgia light,

and in a flourish, he flies back into his story.

She observes this from the middle of the Chattahoochee

in a boat she stitched together from bee wings,

Paraffin wax, and the names of her favorite clouds.

Summer’s End

We were boys somewhere between Star Wars

and the swarm of girls on purple bicycles

buzzing in driveways and knowing far more

than us about the world—these oracles

of the neighborhood, who had begun in spring

a coordinated campaign of whispering

sundresses and secret plotlines, quoting

made-up love songs and explaining nothing.

John Chancellor warned that Skylab was falling

out of its orbit, so we searched for fiery signs

together, forgot our names and our parents calling

us to our homes among sleeping roses, silent pines.

NASA said the wreckage rained over Australia,

but I swear we saw it blazing over Alabama.