Interview with Lee Durkee by Christina Morse

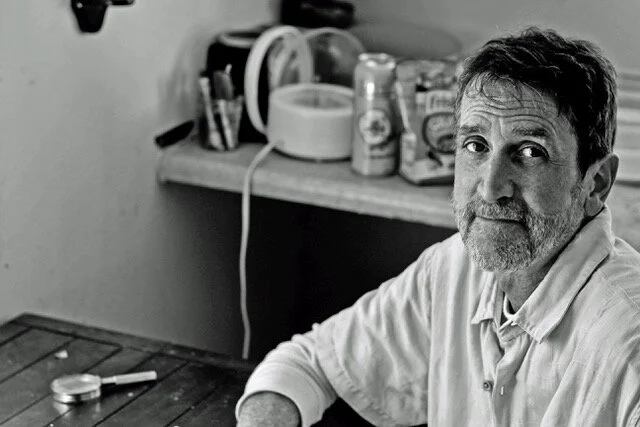

/Lee Durkee was born in Hawaii and raised in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He is the author of the novels Rides of the Midway and The Last Taxi Driver. His stories and essays have appeared in Harper’s Magazine, the Sun, Best of the Oxford American, Zoetrope: All-Story, Tin House, New England Review and Mississippi Noir. His forthcoming memoir, Stalking Shakespeare will be released in 2021. He currently lives in Oxford, Mississippi.

CM: The Last Taxi Driver moves fast. But it’s also dense with details that grab and hold you. It concerns a day-and-a-half in the life of Lou, cab driver in a small university town in Mississippi. Upon the first read, I was amazed. The second, allowed me to see the threads that make this book gel. Your characters are vivid. Your observation of human behavior translates into strikingly original metaphors that are hilarious, insightful, painful and squirm-worthy. Most people will see someone they know in these pages, but I wonder if they will also see themselves. What makes these characters distinctive Mississippians for you?

LD: I guess it would vary character to character whether I even think that’s true. I’m not a distinct Mississippian I don’t think, so the character, Lou, who is somewhat based on me is influenced by Vermont tremendously and other places like Hawaii. Some of the characters are more Mississippian than others but I would like to think of the term Mississippians’ character as somebody who is educated in Mississippi because as the book argues, facetiously at times, that’s more than anything what defines us as Mississippians. We’re products of our hopefully integrated education system, and we’re also victims of it because it’s a notoriously bad system and I think that affects our personalities, it affects our confidence and it affects our pocketbooks. It affects the job market we have available to us.

CM: Readers and critics might classify The Last Taxi Driver as dark comedy. It is one of the funniest books I’ve ever read, but you have a theme of injustice and inequity among our most compromised citizens. Your characters address poverty, racism, mental and physical disabilities, sexual abuse, alcoholism, bullying, and ageism. You grew up in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, a conservative southern town, moved away when you were nineteen, and eventually came back after many years. How do you feel social justice issues of race and economic inequality stack up with other places you have lived? Do you feel things have improved or worsened in Mississippi during your absence?

LD: I lived in Vermont for quite a long time and the culture shock of moving back to Mississippi from Vermont was pretty severe. I think a lot of the social justice issues that Lou has and that the book might have as well come from my time in Burlington, Vermont, an area in which social justice was light years ahead of anything conceived in Hattiesburg, at least. One of my first experiences in Vermont was wandering through a park for a political rally and listening to this guy, Bernie Sanders, give a speech and my mouth must have hit the ground. I didn’t know politicians said things like that. That was the environment in Vermont and I was there for at least seventeen-and-a-half years. I just could not stand another month of winter so I thought I would come down to see how Mississippi had changed. I liked Oxford and I was here many years earlier on a book tour. I was going to come stay in Oxford and I stopped in Tupelo because it had a beautiful name and I was hungry. The woman sitting next to me at a franchise bar was from Hattiesburg as well. We started talking and she said her mom taught at Lillie Burney school which was one of the public schools on the poor side of town that I got bussed. So I was like, “interesting conversation, wow.” She talked about how much her mother hated that job and then she asked me where I was raised in Hattiesburg. I told her on Mandalay Drive near the Thames school and she took a pause and she goes “Oh I know that area. The N words have it now.” So she threw out the N word and I looked at the clock. I had been back in Mississippi less than 45 minutes, right? I had come here thinking Mississippi had progressed. I projected Vermont onto the world and Mississippi and when I got here what I saw was Mississippi really didn’t seem to have changed much at all. Obviously it’s changed, obviously it’s improved, it’s just slow steady improvement at best. But I haven’t seen much improvement from when I was a kid. Oxford, where I live now, makes that question a little hard to answer because Oxford doesn’t have much in common with Mississippi. Oxford has money, its education system has money, and its gentrified which is not good, nor is it typical of Mississippi. Black people live outside of town and my job was to bring them to work every day in the cab. So you know, Oxford is nothing like the Mississippi I knew growing up.

CM: There is a passage in the chapter entitled “Mississippi!” where Lou imagines revisiting his home town. I felt it is one of the most powerful moments in the book. Would you comment on this passage?

LD: That was a very difficult passage to write, and it was an even more difficult passage to get through the whole publication process because I’m a boomer, white, male Mississippian and my book is being put out by a pretty cutting-edge press. That was a worrisome chapter because it portrayed some white kid being victimized inside the school on the black side of town. That’s not an easy thing to write about as a middle-aged white guy writer. It’s uncomfortable. I went through a lot of drafts. The people at Tin House were concerned about it. I don’t blame them. I was concerned about it. I’ve never worked harder on anything than that passage and I lost a lot of sleep and worry over it. Nobody has voiced any objection to it that I know of. I was terrified there would be repercussions to writing about that. I’m grateful to Tin House for helping me see it though different eyes. The passage itself was something I experienced and so it was difficult to be told that I couldn’t describe it exactly as it happened and I had to make changes that were actually erasing the things that I had experienced in describing this really traumatic event. A part of me understood that and a part of me thought huh, that’s an odd thing to have to do. But I think all the correct decisions were made by Tin House and subsequently by me. I’m grateful they guided me through that passage and people seem to like it so it was worthwhile to get feedback on it and it was nice. Just like it was nice to get feedback from you on the social concerns of the novel which is something people really haven’t touched on as much. It’s been reviewed well; it’s been reviewed a lot but that’s not something that seems to come up.

CM: The Mississippi! passage was harrowing but it was so moving. My jaw was open after I finished that passage and I just had to close the book, sit there and think about it for awhile. Later I moved on but that was such a brave, amazing and wonderful passage. I haven’t seen anything quite like it.

CM: Buddhist philosophy is sprinkled throughout your book, especially the idea of the illusion-like nature of our daily experiences. You quote from the Book of Eights translated by Gil Fronsdal about how Gotama Buddha shows human contentions as “a wilderness of opinions.” How does Buddhist philosophy play out in The Last Taxi Driver? How and where did you discover Buddhism?

LD: I became a Buddhist after I left graduate school in Syracuse—after I failed graduated school in Syracuse. I came back to Arkansas and got my degree eventually there. My girlfriend at the time was a Buddhist and got me interested in Buddhism. I’ve been a Buddhist ever since. She was at the time pretty esoteric. Her teacher was in Vermont of all places. She combined her native Cherokee teachings with Tibetan Buddhism. This is what her interest was so this is what I was first shown. It was tantric Buddhism, chakras, and that became what I was interested in for the next twenty years. Tantric Buddhism was a huge part of my life, but it also got me interested in Tantric Hinduism which became equally important to me. In a sense, this book, with its emphasis on the Book of Eights doesn’t refute that world but it hopefully gives voice to a side of Buddhism that you don’t hear about as much in America. And that Buddhism is based on the actual teachings of the original Buddha that used to be called small wheel Buddhism. The Book of Eights, and the commentary of it by Fronsdal, was a discussion on what is believed to be the oldest poems of the Buddha that reflected his original teachings most honestly. And that was simply the idea of conceptual thinking. It had nothing to do with Gods or rebirth or reincarnation, because the original Buddha as we see him in these poems had no interest in those things. He saw them as distractions. He didn’t denounce the belief of God; he didn’t support it. He didn’t care; it wasn’t his issue. It was the issue of the zeitgeist around him and that’s what he was born into, a world that was consumed with the idea of reincarnation. That was not his idea and he responded to it by saying don’t get attached to anything and you don’t have to worry about being reincarnated. That was the goal of a lot of the Hindu practitioners at the time—not to be reborn on earth because earth was perpetual suffering. Gotama was much more interested in what we call today “conceptual thinking.” Cognitive therapy is the professional name of it— the idea that everything we see, we immediately wrap inside concepts. So, if say you’re a writer from the northeast and you’re about to see me interviewed and you know I’m 60 years old, you know I’m from Mississippi, you know I’m white, and you’re immediately going to wrap me in concepts even before you meet me. Those concepts include everything you think about boomers, and everything you think about white Mississippians; we do that with everything. What we see is Maya, which is a world of illusion, because we’re seeing our concepts.

CM: I love the subtle layers of Buddhist themes in the book. Samsara is a Buddhist concept that translates as the endless cycle, or wheel, of suffering. Lou is clutching his steering wheel while driving his cab in wheel-like circles all around town picking up challenging personalities that also cycle in and out of Lou’s day while causing him to cling to his opinions of aversion, attachment or indifference. I am very curious about a three-legged deer in the book whose name is Maya. You referenced Maya earlier as illusion. How do you see Lou relating to Maya, this wounded, three-legged deer?

LD: A real life three-legged deer had been hanging around my backyard for months before I started writing the novel and had recently disappeared, so I wanted to remember her in my book. But Lou is the one who named her. The name Maya didn’t come to me until I was writing in Lou’s voice. He identifies with her plight and impending doom and is very fond of her, but at the same time, Lou is terrified of deer and worries that is how he will die —the deer through the windshield—so, in a sense he is probably also hoping to get in favor with the Great Spirit God of All Deer by being kind to the three-legged doe. And that brings up another concept central to Buddhism: the real motives behind our kindnesses and the idea that merit is not created without proper motive aka compassion. You can build an orphanage but if you did it just to name it after yourself then you still suck. To be honest I’m not sure why she’s named Maya. Buddhism was certainly on Lou’s mind. The understanding of the existence of great suffering within all beings is the first noble truth of Buddhism. But there’s nothing illusory about the suffering of the three-legged deer. If anything, she would seem to represent a harsh realism and not the illusory realm you described so well in the question. It’s a pretty name, though, and I suppose that’s why he chose it. Maybe he wanted her to be moving toward some better realm than this one. There is a great solace, at times, in the notion that our world isn’t real.

CM: There are so many great quotes in your book. Here are just a few of my favorite ones. Feel free to comment.

“When I hit a fresh red on Barbour and Lott, the second-most evil traffic light in town, it happens. I can feel it like a werewolf sniffing moonlight. My nails begin to grow, and I fiddle with my collar and mutter ‘Jesus, it’s hot in here.’ as the goat horns slowly emerge from my skull.”

LD: The first thing that comes to mind is “Jesus it’s hot in here.” It is an allusion to the American Werewolf in London just before he turns into a werewolf and I love that movie. Other than that, it just was part of my daily transformation that really bothered me about myself. As a cab driver I was working twelve hour shifts and every day I would lose myself inside road rage at a certain time, exhaust myself with it, then come out at the other end almost beat up by it, but at least not doing it anymore. I really couldn’t stop it. I wanted to put that into Lou’s character because everybody I’ve talked to can relate to road rage to some extent. And yet road rage is horrible; it’s like becoming a beast, an animal, it’s as primal as it gets. It really bothered me that I couldn’t control it. It made me reevaluate who I was.

(Referring to Lou’s girlfriend he’s trying to break up with) “We are ghosts from different dimensions who happen to overlap in our existential existences and only materialize into each other’s lives to scream and spit at one another before disappearing again. Of all the types of loneliness I’ve endured this is by far the worst, with none of the solace of solitude and the forever feeling that even the air you exhale disapproves of you.”

LD: I wanted to write a scene that reminded me of the opening scene of the movie “Down by Law” by Jim Jarmusch. In that scene, Tom Waits and Ellen Barkin are having this horrible argument. He’s a DJ and she’s smashing his records against the wall, throwing his clothes outside. That’s what I wanted to convey, that type of a moment in your relationship where it’s clearly obvious that these people need to go their separate ways. And it’s not a case of somebody’s right and somebody’s wrong . It is a case of this is an unhealthy situation for both people.

“It feels like I’m standing in an ant bed of deja vu.”

LD: I’ve been sitting on that analogy for years and finally used it. I know that I’ve almost used it so many other times that I can’t even recall the rest of the sentence, the context when I used it. I thought I used it before then those things just didn’t get published.

“I close my eyes and—remembering all the evil thoughts I’ve harbored against Zeke—recalling what an asshole I was to head-butt Stanton—I take a deep breath filled with sea monkeys and then howl them through the windshield.”

LD: Lou feels a lot of guilt and maybe he feels more guilt than he should. I think there are two different perceptions of Lou and that is his perception of himself—he’s very hard on the world and he’s very hard on himself. But I think the reader hopefully likes Lou more than Lou likes Lou. Lou’s desire to be a better person also fills him with self-loathing. Lou, at one point later on in the book, can’t find anybody that he’s better than and that really bothers him.

CM: The description of the two elderly men Lou picks up from the hospital is haunting. He agonizes over how they will be cared for once he drops them off at their homes. The image of the farmer in his isolated run-down trailer with grasshoppers everywhere will stay with me for a long time as will your quote, “These guys are as desiccated as old mushrooms you could kick into dust.” Since you worked for a stint as a taxi driver how were you able to cope with experiences like these?

LD: If you cope with it at all, you cope with it like Lou copes with it. Maybe it comes out via road rage, guilt and things like that. Those things really happened to me. I did drop that guy off, there were grasshoppers, the trailer was nothing, there was no electricity, it was in the middle of an overgrown field. It was hot in there and I just left him there and like Lou then I remembered, “Oh, ok. I’ll call the hospital and make sure his brother is gonna look after him.” But on some level we know that’s going on around us even before the pandemic. People are suffering horribly and we all cope with it in one way or another. If we didn’t have that mechanism we couldn’t watch the news at night. But one way you cope with it is dark humor and I think that allows you to go on. I don’t know how I can survive without dark humor and without cursing. I would probably have been dead twenty years ago if it weren’t for cursing. It’s a release valve.

CM: Near the end of The Last Taxi Driver, Lou has an epiphany about his own “wilderness of opinions.” Would you comment on that?

LD: Yeah, I think he realizes, and it goes back to the idea of conceptual thinking. I think it becomes more than just an intellectual idea to him. The power of conceptual thinking —I think he internalizes it at that moment, hopefully for his benefit.

CM: You’ve said you are compelled to write even if you don’t publish. To what do you attribute your determination to continue as a writer when faced with personal setbacks, the publishing world and the irony of two catastrophes (9/11 and the COVID-19 pandemic) at the same time you released both of your books?

LD: I think there is a tendency to want to paint something as noble but when you are dealing with something you’re compelled to do, it’s not work, therefore it’s not noble. It’s a compulsion and it’s something I love doing. It’s my favorite thing I’ve ever done aside from maybe playing soccer. I love to write so why would I quit? It’s how I understand myself; it’s what I do in the morning if not all day and what else would you do with caffeine but write? It’s just like second nature, it never crossed my mind to quit writing.